A 16-year-old European hedgehog called Thorvald has been crowned the oldest in the world, smashing the previous record by seven years.

The male hedgehog lived near the town of Silkeborg in the centre of Denmark. Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen, from the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at Oxford University, who led the Danish Hedgehog Project that discovered Thorvald, said she was overwhelmed when she discovered how old he was.

“I cried tears of joy that I was holding an individual that lived for 16 years. That’s really good news for conservation. Under the right conditions, hedgehogs can live for 16 years – it’s amazing. All my colleagues were laughing at me because they thought I was being so emotional,” she said. The previous record-holder was thought to be a nine-year-old female hedgehog in Ireland, identified by researchers in 2014.

Unfortunately Thorvald died at Animal Protection Denmark’s wildlife rehabilitation centre in Silkeborg in 2016 after being set on by a dog, a common cause of hedgehog mortality. Rasmussen says dogs should be kept on leads or locked up at night when hedgehogs are out. “It’s very sad that he lived for so long and then died after being attacked by a dog.”

Thorvald was one of almost 700 dead hedgehogs collected by 400 volunteers as part of the citizen science research. They also found a 13-year-old and an 11-year-old, according to the paper, published in the journal Animals.

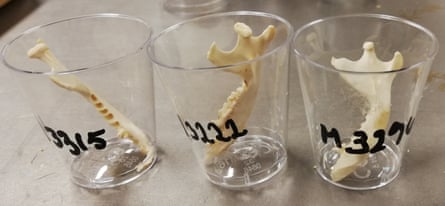

The bodies were sent to researchers who worked out how old they were by counting the growth lines in their jawbones, rather like counting tree rings. This research is significant as hedgehogs numbers are in decline across many European countries, their loss driven by habitat destruction, intensification of agriculture, road traffic incidents and the fragmentation of populations. In the UK, rural populations have fallen by as much as 75% in some regions in just 20 years.

Thorvald had infected bite wounds on his stomach and back; infection had also caused his penis to become extremely swollen. “It was the largest hedgehog penis I’ve ever seen,” said Rasmussen, who said that otherwise the hedgehog was generally healthy – indicating that the mammals could live even longer than 16 years.

However, the average age of the animals studied was two, with a third of hedgehogs dying before the age of one. Researchers believe that if hedgehogs can get over the tough first years they could go on to have long lives and produce offspring for several breeding seasons. “This may be because individual hedgehogs gradually gain more experience as they grow older,” said Rasmussen. “If they manage to survive to reach the age of two years or more, they would have likely learned to avoid dangers such as cars and predators.”

They found that male hedgehogs lived longer than females – reaching an average of 2.1 years, as opposed to 1.6 years – which is unusual in mammals. Rasmussen said: “The tendency for males to outlive females is likely caused by the fact that it is simply easier being a male hedgehog. Hedgehogs are not territorial, which means that the males rarely fight. And the females raise their offspring alone.”

More than half were killed when crossing roads, with deaths peaking in July when males and females are walking long distances trying to find mates. Another 22% had died at rehabilitation centres after being collected by the public and 22% of natural causes in the wild.

Counting growth lines on jaw bones is an effective way to age hedgehogs because their metabolism slows down during winter and bone growth is reduced or stops altogether. One line represents one year.

Another key finding of the paper was that inbreeding did not appear to reduce their life expectancy. Finding an unrelated mate is increasingly a problem for hedgehogs as populations shrink.

Rasmussen said: “Our research indicates that if the hedgehogs manage to survive into adulthood, despite their high degree of inbreeding, which may cause several potentially lethal, hereditary conditions, the inbreeding does not reduce their longevity. That is a rather groundbreaking discovery, and very positive news from a conservation perspective.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features