China’s officials have used every tool at their disposal to muzzle criticism of the crimes the country committed at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, but on the 30th anniversary of the massacre, the events the government has tried for decades to erase from the pages of history are deservedly back in the spotlight.

It’s not a moment too soon. Despite international condemnation, China has not stopped its war on the truth, or its crackdown on free speech. The Tiananmen anniversary inevitably focuses the world on a fundamental truth about one of the biggest global superpowers: Despite China's spectacular economic success, its leaders rely on widespread repression to secure their grip on power.

Despite its spectacular economic success, China’s leaders rely on widespread repression to secure their grip on power.

Since the 1989 massacre, China has deployed both new and old methods of oppression, as many of the world’s leaders look the other way. The regime imprisons its critics, makes access to unfiltered information increasingly difficult and has rounded up hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of its Muslim citizens in what advocates are calling concentration camps. Most of the prisoners are from the central Asian province of Xinjiang. The government apparently finds them suspicious or potentially threatening because of their religious beliefs. Xinjiang’s entire population lives under tight surveillance. Those who enter the gulag endure brutal conditions, according to United Nations experts, who say inmates are tortured as the regime tries to brainwash them.

And the world is, by and large, not paying attention.

The regime dreads the Tiananmen anniversary. The subject is banned in China: Officials just shut down Wikipedia, and censors at Chinese internet companies say there’s a ferocious campaign to block all searches related to the 1989 events. Fearing an outbreak of protests, universities have reportedly been placed on high alert. Student activists have reportedly “disappeared.”

As China has grown wealthier and more powerful, the rest of the world has become meek. This reluctance to press President Xi Jinping extends to the United States, where President Donald Trump is focused on trade, with seemingly little interest in human rights.

It was not always so. The events at Tiananmen Square were so horrifying, that for a time China became a global pariah.

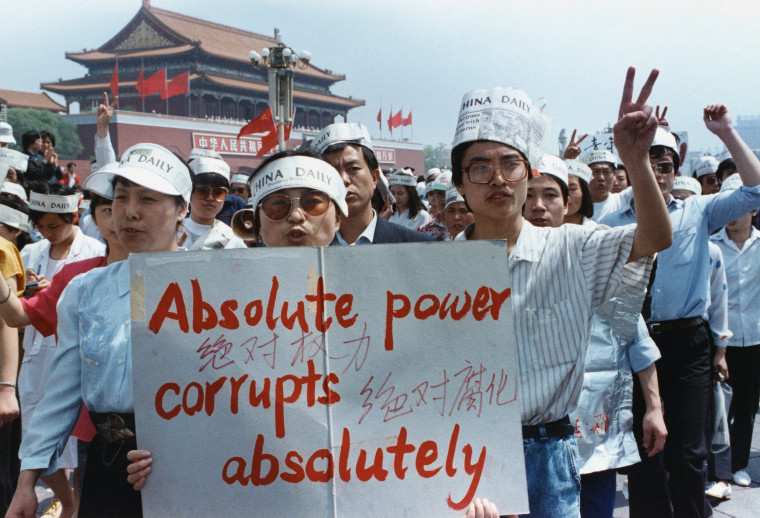

Thirty years ago, amid national protests demanding more freedom, Beijing crushed a massive pro-democracy protest in Tiananmen, the heart of the capital, in full view of the international news organizations gathered for a summit between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his Chinese counterparts.

Idealistic students converged in the square, honoring a Chinese reformer who had just died. They demanded political reforms, an end to media censorship and a solution to official corruption. The square grew crowded as tens of thousands built a makeshift version of the Statue of Liberty, the now-iconic Goddess of Democracy as they called it. It would soon lie in pieces.

But instead of negotiating to defuse the situation, the government decided to crush it. An AP photographer captured the now indelible image of a lone man holding shopping bags and standing defiantly before a line of tanks; the world watched live as censors shut CNN’s transmission. But nothing stopped the tanks from rolling over the students, as soldiers fired live rounds. When it was all over, hundreds, perhaps thousands, lay dead.

Many young Chinese have not heard about Tiananmen. Authorities never mention the event. In a rare exception, China’s defense minister, Gen. Wei Fenghe, defended the crackdown at a summit in Singapore this week, calling it the “correct” decision.

The event marked a turning point. Until then, China had engaged in a gradual process of economic and political reform. After Tiananmen, the Chinese Communist Party made the “1989 Choice,” severing political from economic reforms. So while subsequent governments would work to drastically transform the economy, opening it up to global trade and market forces, politically the opposite was true. Instead of liberalizing, the government smashed dissent and criticism. It imprisoned student leaders and made sure no new powerful critical voices were allowed to rise without suffering a devastating cost.

China was no longer a communist country. Instead, it became a one-party authoritarian state functioning under state-controlled capitalism.

China’s entry in the World Trade Organization in 2001 helped turn it into the world’s factory, with spectacular growth. Washington decided to ease tensions, claiming that “constructive engagement” would help persuade the regime to open up. But the opposite happened.

Many Chinese willingly accept the bargain, seeing the lack of personal political freedom as a small price to pay for vastly improved living standards. And the regime has sought to bolster popular support by engaging in a concerted campaign of nationalism, stoking patriotic feelings and equating them with allegiance to the Communist Party.

Patriotism does not make censorship tolerable, and many young Chinese chafe under China’s asphyxiating censorship machinery.

But patriotism does not make censorship tolerable, and many young Chinese chafe under China’s asphyxiating censorship machinery. For the fourth consecutive year, China was ranked the world’s “worst abuser of internet freedom” by Freedom House. China needs to control what its people see and read because they might hear the details of what authorities are doing in Xinjiang, for example, where a network of what looks very much like concentration camps now holds, by some counts, anywhere from 1 to 3 million prisoners, mostly ethnic Uighurs.

The government claims they are voluntary vocational training centers, part of a program to counter extremism. Uighurs are Muslim. The government may not want the public to learn more about the extent of its surveillance program, or the ruthlessness with which it suppresses political criticism. And repression is rampant in other minority areas, such as Tibet. Even prominent citizens can disappear into the government’s repressive gulags.

China is incredibly powerful, but its leaders remain afraid of losing that power. And hardly anything scares them more than the echoes of Tiananmen.