The anti-fascist artist who used his work as a weapon

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by John Heartfield

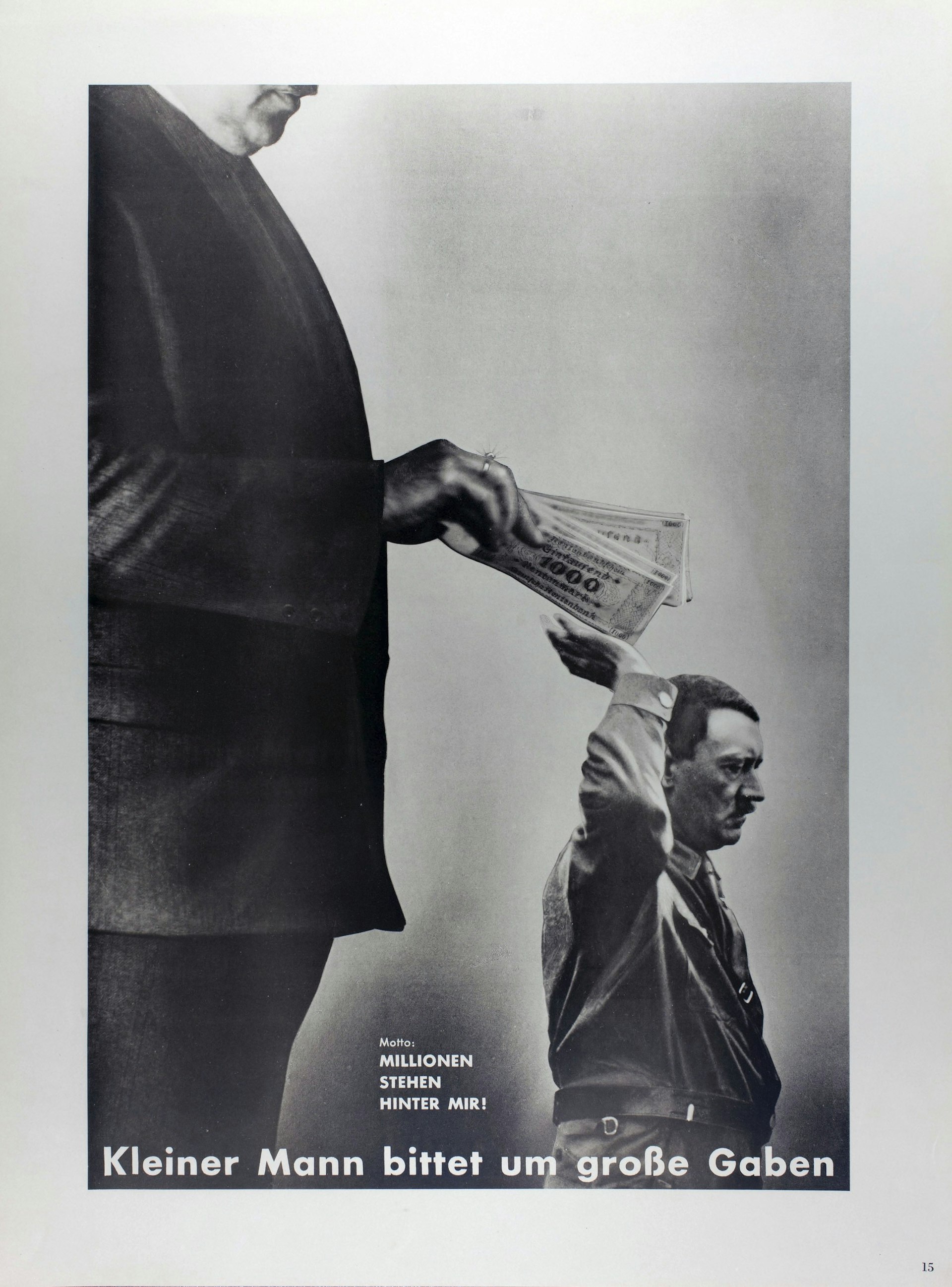

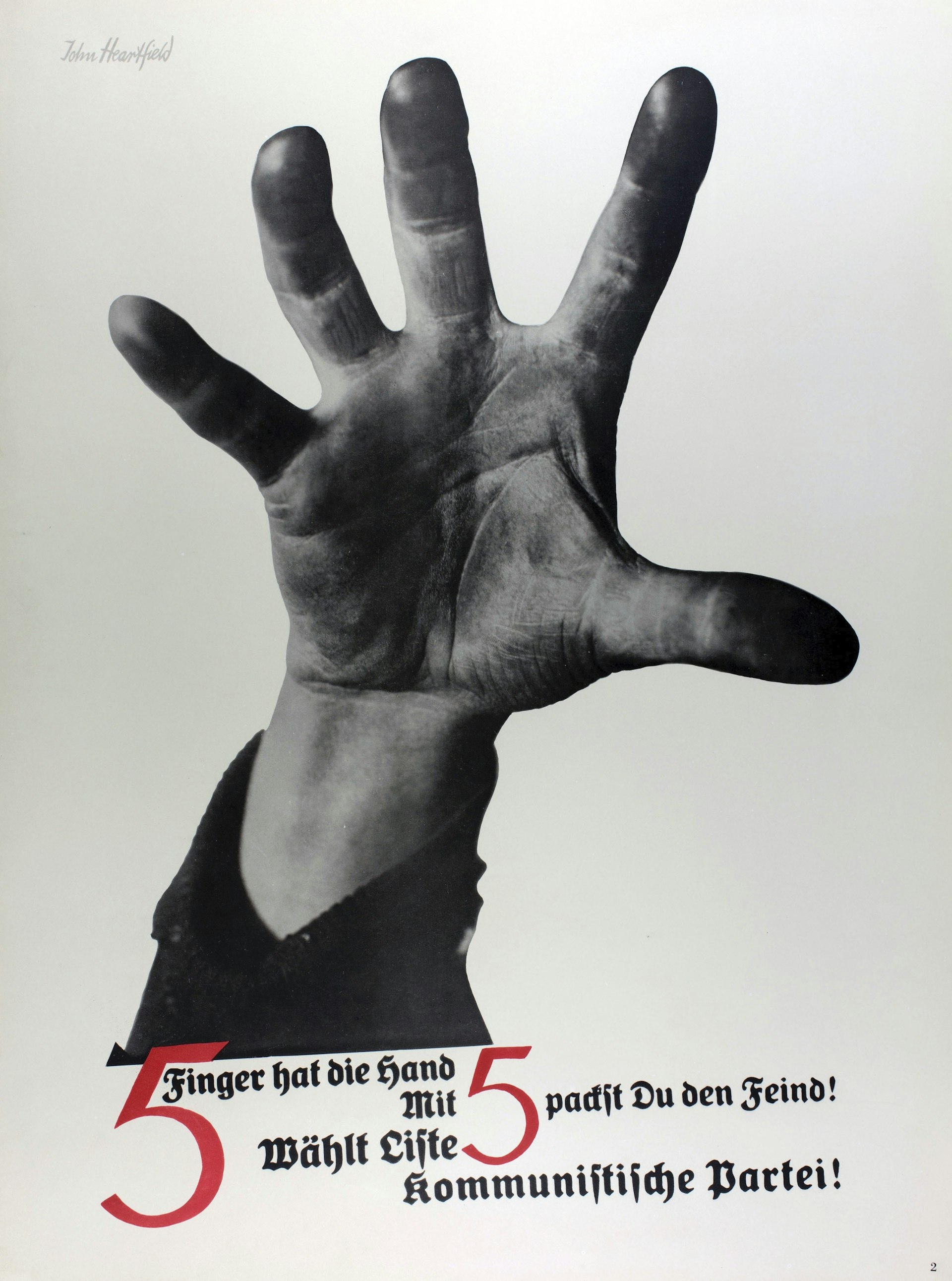

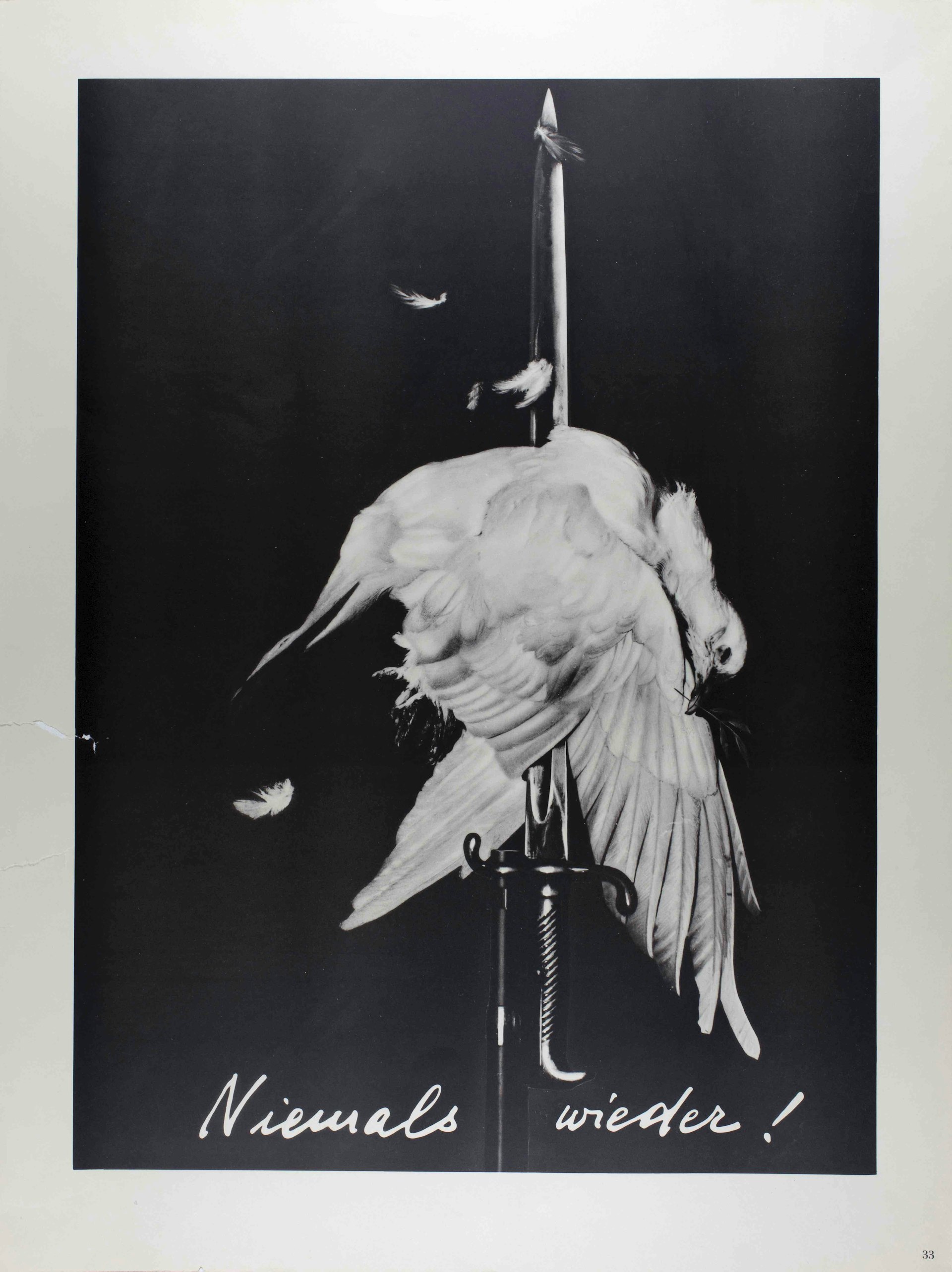

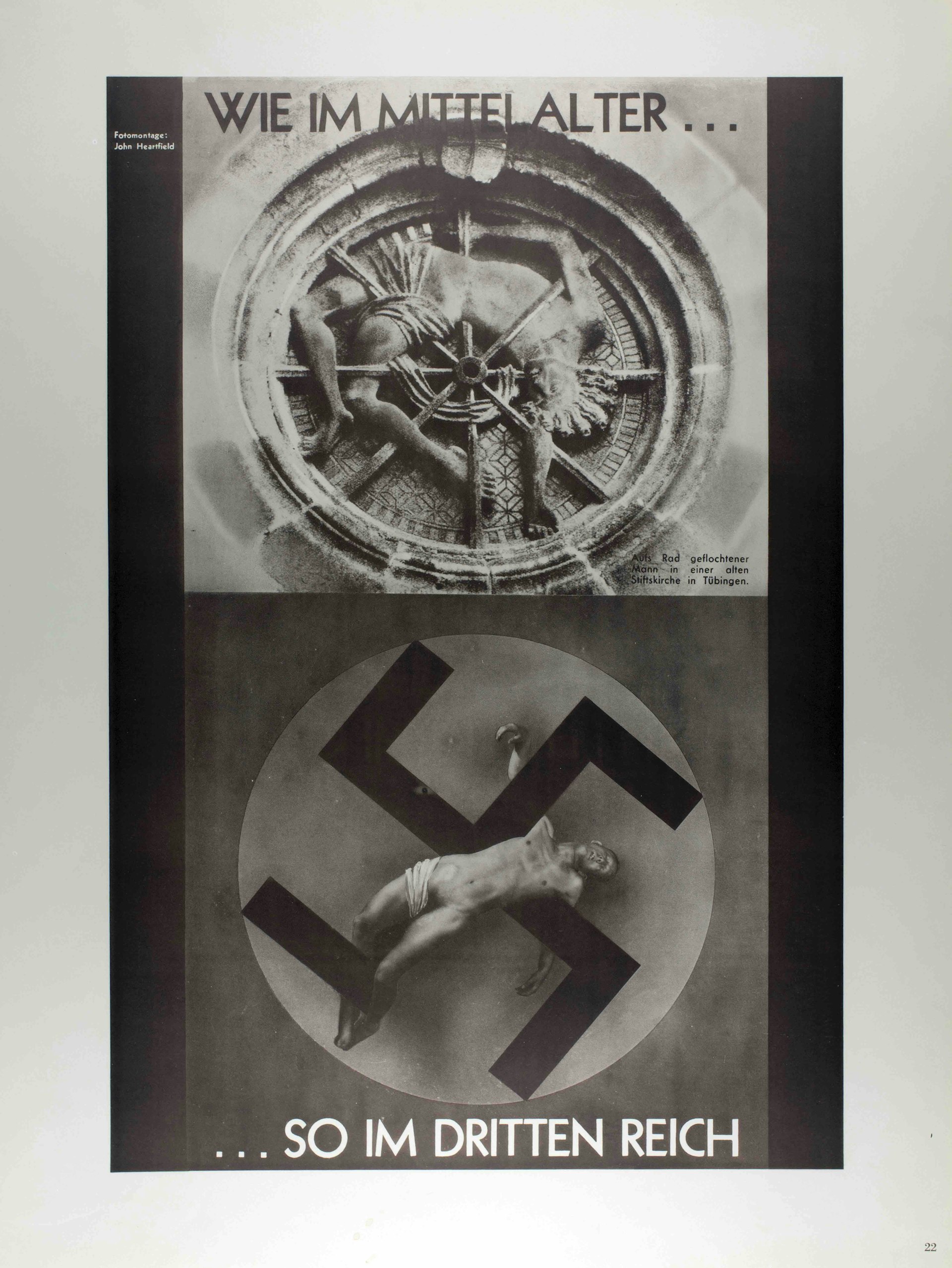

Armed with scissors, paste, and stone cold reserve, German artist John Heartfield (1891-1968) used art as a weapon to fight Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in the 1930s. His acerbic photomontages, which subverted Nazi imagery to reveal the rising political threat, appeared on the cover of communist magazine Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung – they were seen by millions of people on the newsstand, and in their homes.

Now, thanks to a new exhibition, a new generation of audiences are set to be introduced to his work. Titled Heartfield: One Man’s War, the show explores how the artist risked his life in a propaganda war where he played the part of the anti-Leni Riefenstahl. Trained in advertising, he understood better than most the power of image and text held in swaying public thought.

As an impassioned communist radicalised at the end of World War I, Heartfield recognised photography was the most modern and persuasive visual language available at the time. He believed that his photomontages had the power to change public discourse, while simultaneously reclaiming modern art from the ineffectual idea of “art for art’s sake”.

“Heartfield was really good at finding photographs he felt were iconic for certain problems whether in politics, society, or culture,” says Andres Zervigón, Professor at Rutgers University and author of John Heartfield and the Agitated Image. “He knew exactly which photos to appropriate, and then he would juxtapose these distillations with each other. One commentator at the time said that Heartfield’s photomontages were ‘photography plus dynamite’.”

Hitler, who deftly understood the power of the press, coordinated his rallies with the camera in mind. Heatfield took great care to foil his opponent at every turn, using Hitler’s carefully crafted image against him.

Heartfield famously cut Hitler’s head out of a press photograph where he was giving a speech and placed it atop of another photograph of a chest x-ray. He then Heartfield showed gold coins slipping down Hitler’s agape mouth and into his belly, before adding the slogan, “Adolf the Superman swallows gold and spouts junk.”

The Nazi Party was not amused, though they waited until they officially came into power in 1933 before making their move. Heartfiled got caught at a printing press making a poster, but managed to escape. He bolted back to his apartment, heard the Gestapo coming, jumped out the window, and eventually fled over the mountains to Prague.

The Nazi Party was not amused, though they waited until they officially came into power in 1933 before making their move. Heartfiled got caught at a printing press making a poster, but managed to escape. He bolted back to his apartment, heard the Gestapo coming, jumped out the window, and eventually fled over the mountains to Prague.

At one point, he reached number five on the Gestapo’s most-wanted list. “Heartfield was high on the list of opponents the Nazi wanted to execute, as he was on Stalin’s list of people – because he was seen as not sufficiently towing the line,” Zervigón says.

Both Hitler and Stalin recognised Heartfield’s impact. “Heartfield wasn’t only reflecting the perceptions of politician but initiating further debate about their politics. It was activist art because he could intervene at a national level.”

A true testament to Heartfield’s influence occurred in 1937 when the Nazis refused to include his work in the notorious Degenerate Art Exhibition. “Heartfield’s work was too powerful to be satirised or humiliated in that show,” Zervigón adds. “It was just too dangerous to share it with the public.”

Heartfield: One Man’s War is on view at Four Corners in London through February 1, 2020.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.