COVID-19 and Immersive Installation: Annette Messager’s “Penetrables"

/Historically, strategies of representation have been used to produce an image of the human body that is comprehensible and systematic. How is the body represented at moments of global crisis, and how can an artwork unsettle such foundations within the realm of representation? How do visual forms of the body shape our conceptions of selfhood?

In the 1990s, French artist Annette Messager began creating what she calls “penetrables,” large-scale installations composed of hanging elements, that the viewer enters into and walks around within.

The earliest of these, Penetration (1994), presents an array of hand-sewn anatomical organs, made of cotton and stuffed with wool, polyester, and nylon. About 100 of these oversized human organs are attached to an armature near the ceiling by knotted angora wool strings, so that they dangle at varying heights around the viewer’s eye level. There is enough space for the viewer to walk between the organs, and approach each individually. The forms and features of the organs are simplified, enlarged, and rendered in bright colors. They appear distinct and loyal to their references so that even one with a basic understanding of anatomy can identify many of them: liver, stomach, intestines, gallbladder, pancreas, thyroid, colon, lungs. Both male and female reproductive systems as well as three fetuses at different stages of development are included.

Annette Messager, Penetration (Pénétration), 1992-94. Sculptures, installation, cotton stuffed with polyester, angora wool, nylon, electric lights. installation (variable). Monica Sprüth Gallery, Cologne (1994-95). Image from Annette Messager: the messengers, Prestel, 2007.

Veins and arteries decorate some organs like the heart. The circulatory system is rendered in red and blue, demonstrating the exchange of oxygenated blood from one side to the other. Penetration’s iconography calls to mind a specific kind of image: the anatomical diagram or illustration, which presents a bodily system, such as the skeleton or muscles.

Anatomical illustrations are positioned as tools for producing and understanding the composition and functions of the body, and are widely used in education, surgery, and medical research. The bodies are typically shown in cross-section, revealing the usually concealed interior spaces. The illustrations’ components are simplified, abstracted, and enlarged and irrelevant information is excluded. All this is done so that a single system or process can be clearly described and understood.

For thousands of years humans have been interested in how the interior of the body works, describing and imaging it in a wide range of media and artistic styles. The visual has served to assert scientific authority by producing a canon of the body that text alone cannot. The illustrations have most often been made through close collaborations between artists and medical professionals, who both actively produce and shape scientific knowledge. Today, anatomical illustrations are understood to present what is actually inside the body, naturalized as accurate, neutral, and objective scientific documents.

If we consider Messager’s installation more critically within this history, several interventions stand out. Here, the body is fragmented. It is not a functional system that we can follow to resolution. The organs are isolated and their functional purpose and relation to each other is unclear. A gray brain hangs near a colon and liver, and the ventricles that would carry blood from the heart to the rest of the body are severed, stopping abruptly where they might connect to an artery.

Messager also multiplies certain elements; for example, three fetuses and two spinal columns. With these aesthetic choices, she indicates that this body’s interior is different than the one that science posits, raising questions about its neutrality.

The installation’s lighting also sets Penetration in contrast to the legible anatomical illustration. Between three and seven bare lightbulbs are suspended amongst the organs, hung a little below them, so that they cast enlarged shadows that move over the gallery walls. The shadows are produced by a few different light sources simultaneously, so that a single form in the installation appears more than once in shadow. The bulbs intensify the subtle movements of the objects, creating a theatrical environment. The organs sway and twist as they are influenced by changes and movements of air and bodies in the area. In this dreamlike—or nightmarish—space, time slows and gravity is suspended.

Penetration installation view from Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia from the exhibition annette messager: motion/emotion, july–october 2014. image from exhibition essay by curator rachel kent.

A primary motivation behind the production of anatomical illustrations is to understand illness and healing, and they are often used in public health and propaganda campaigns. Visual representation can take on a heightened importance at times of crisis, when the human body is in a vulnerable position. In the past few years, a particular medical illustration has become a prominent force in visual culture—the representation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

As the coronavirus began to spread across the planet in early 2020, it was covered widely in the media in tones of alarm and panic. We did not understand COVID-19’s mode of transmission, or have any effective treatments for the disease. Our bodies were transformed into potentially lethal threats and fear and anxiety were palpable in the public. We were desperate to understand how the virus spread, and how we could defend our own bodies from this undetectable threat. We turned our gaze on the virus itself. Even in comparison to other microscopic viruses, the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen is tiny; at one one-hundredth of a nanometer in diameter, it cannot be detected by a standard light microscope.

Transmission electron microscopic image of an isolate from the first U.S. case of COVID-19, formerly known as 2019-ncov. cdc / cynthia s. goldsmith and a. tamin. public domain.

Taken from an isolate of the first U.S. case of COVID-19, this transmission electron microscope scan is the first image of the virus. It was released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the spring of 2020. It is not a particularly striking visual. In the fuzzy, black and white image, it is unclear what is pictured—where the virus is, and if there is an interaction going on. It lacks a center of focus, sense of composition, and directional indication of movement. Though the scan was a scientific breakthrough that was crucially important for the developments of treatments and vaccines, it was difficult for a non-professionalized public to comprehend.

But, months before the electron scan was produced, the CDC had already released the first scientific illustration of the pathogen, which quickly became the public face of COVID-19.

Illustration of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Alissa Eckert, MSMI, Dan Higgins, MAMS. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library, ID # 23312. Public domain.

This image was developed in less than a week by CDC illustrators Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins, their design based on knowledge of other coronaviruses and available research. The pathogen is presented here in full-color and three dimensions⸺a single floating gray sphere covered with yellow and orange membrane proteins and red shrubs that represent the spike proteins that bind to and invade cells in the respiratory tract. The image is composed like a portrait⸺the virus is centered and singular, without distractions. The different components are clarified with bright color and a simple composition. This is the image that was used to communicate the virus’ modes of transmission and infection to a concerned public. Several years on, the image is instantly recognizable to an international audience, and is considered to be the most iconic viral illustration ever produced.

Variations on the CDC image proliferated quickly, appearing not only in public health warnings, but also widely in the news media. Though creative liberties were taken, its basic shape—the spherical membrane covered with protruding spikes—became a visual touchstone for all aspects of the pandemic. It was quickly taken up in many different areas of visual and material culture.

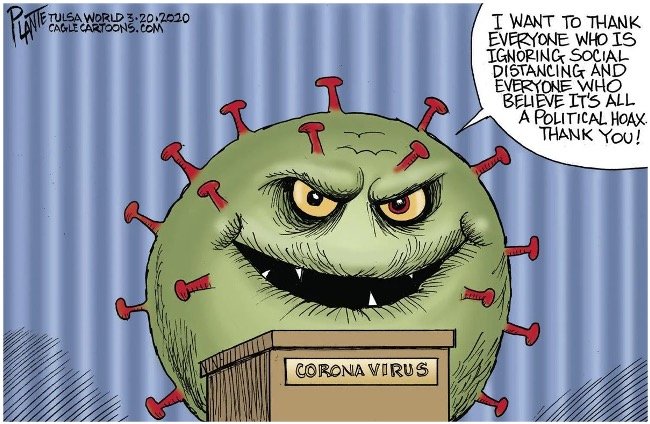

All over the world satirical cartoons in magazines and online personified the virus, connecting it to political events, or making it into a monster with sharp teeth. In street art and graffiti the virus took on different moods and personalities, along with a growing repertoire of symbolic associations.

SEVERAL TELEVISION NEWS PROGRAMS WITH STAGE DESIGN AND ILLUSTRATIONS OF SARS-COV-2. IMAGE PRODUCED IN ADREU-SÁNCHEZ, C., MARTÍN-PASCUAL, M.Á. “SCIENTIFIC ILLUSTRATIONS OF SARS-COV-2 IN THE MEDIA: AN IMAGEDEMIC ON SCREENS.” HUMANIT SOC SCI COMMUN 9, 24 (2022).

CORONOVIRUS INSPIRED STREET ART BY REBEL BEAR, GLASGOW, SCOTLAND.

CARTOON BY BOB ECKSTEIN.

PLANTE, TULSA WORLD, MARCH 2020.

ARTIST: SIZETWO. LOCATION UNKNOWN.

GAZA CITY, 2020.

“YOU DON’T SCARE ME” BY SIWELA, PUBLISHED IN THE CITIZEN, SOUTH AFRICA. MARCH 2, 2020.

We saw cute COVID toys that one could hug or squish, as well as a plethora of virus-inspired cuisines.

CORONAVIRUS COVID-19 PLUSH TOY, DREW OLIVER’S GIANT MICROBES.

TOY BOOK VIRUS SMASHER.

DIY KNITTED COVID VIRUS, ETSY.

A BURGER SHAPED AS THE CORONAVIRUS AT A RESTAURANT IN HANOI, VIETNAM.

MASTER CONFECTIONER TORSTEN ROTH WITH CORONA ANTIBODY PRALINES, ERFURT, GERMANY.

The now-familiar form was notably popular with state police forces, as we saw officers dressed up as the virus, patrolling the streets in many different countries.

In Bolivia, as part of a campaign raising awareness for social distancing, police officers dressed up as goofy viruses with fangs. Here, the costume renders COVID-19 more scary than sweet, but this visible representation is still less threatening than its undetectable, potentially deadly referent. We use visual strategies of representation, abstraction, and anthropomorphism to make the unknown visible and comprehensible, to neatly package our fears into something we can literally see and touch. In these examples and many others, representation is used to temper the perceived danger of the actual SARS-CoV-2 pathogen.

VIRUS-THEMED HEADWEAR ON OFFICIALS IN INDIA.

CHENNAI, INDIA.

POLICE OFFICERS IN INDONESIA.

AN INDIAN TRAFFIC COP IN BANGALORE.

LA PAZ, BOLIVIA, 2020.

A POLICE OFFICER DRESSED IN A COSTUME REPRESENTING THE COVID-19 VIRUS TRIES TO HUG A PEDESTRIAN, WHO RESISTS, ALONG PASEO EL PRADO AS PART OF AN AWARENESS CAMPAIGN ABOUT THE SPREAD OF THE VIRUS IN LA PAZ, BOLIVIA. IMAGE BY JUAN KARITA / THE ASSOCIATED PRESS.

COVID-19 inspires so much public fear partly because it has the capacity to breach the borders of the body. The human sense of self is inextricably linked to a conception of the body as discrete, closed, and individualized. But the body is not as stable as we might like to think—it is actually emergent from and entangled with trillions of different microorganisms that are constantly in flux, moving through and within it. At the microbial level, we cannot be distinguished from the environment at all. All matter—human and non-human—can more accurately be conceived of as a system of multiple and dynamic interactions of microbial cells. Scientific and medical communities are coming to terms with this information, evidenced by new and increasing investment in fields such as microbiome and genomic research. Developments in other areas like immunology and climate science are also increasingly basing their research on this microbial view.

Yet, we cling to the idea of the individualized body, shaped by Enlightenment-era ideals. To rethink the body as entangled with the world can be psychologically disturbing because it unsettles a myriad of established “truths” that identity, agency, will, and human exceptionalism are based on. It calls into question the basic categorical existence of the human, and, therefore, its relation to reality.

For the conception of the body to change, we must dismantle another Enlightenment legacy—the strict division between the arts and sciences. The humanities have a role to play in the development of a new configuration of how we understand what it means to be human. To elucidate an example, take Messager’s artwork, considering the aesthetic experience it offers.

BOTH IMAGES: ANNETTE MESSAGER, PENETRATION, 1993–94. ANNETTE MESSAGER: MOTION/EMOTION, MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, SYDNEY, 2014. CREDIT: TEXTILE GAZETTE BLOG / FLICKR.

Penetration brings the embodied viewer into the interior space of the body, metaphorically and physically enacting the interconnectedness of the body with what is usually considered to be outside of or apart from it. Messager wanted the viewer to be active in the installation, saying that she “wanted people to brush against the organs on view, and venture into that work as if into a forest made of the innards of bodies.” Messager designed the work so that the viewer would come into physical contact with the hanging objects, setting them in motion, and bringing them into contact with each other. The unplanned and uncharted movement of the viewer within the space, and the chance interaction of all the elements reads as a messy web of movement and exchange that cannot be controlled or systematically described.

The embodied beholder also becomes part of the installation in representation—the lighting scheme projects silhouettes not only of the organs, but also the visitors, on the gallery walls. As the visitor moves within the installation, their enlarged and distorted shadow calls attention to their presence, and heightens the perception of their movements. The visitor is enmeshed in the installation—one element among many, both physically and in representation.

Messager invites the viewer into a truly horrifying scene—the inside of the body, wherein they encounter the self in pieces. Penetration calls on a powerful, inward-looking anxiety by putting the viewer inside of their own interior. We don’t like to think about the body this way; it can make us feel uncomfortable. Here, Messager’s installation calls attention to the function of representation, asking how natural it really is to think about only the digestive system of the body, as a textbook might illustrate it. In the context of experiencing an installation, Messager offers us an opportunity to think about these conventions and how they may have influenced us.

Annette Messager, Penetration (Pénétration), 1992-94. sculptures, installation, cotton stuffed with polyester, angora wool, nylon, electric lights. installation (variable: 500 h x 500 w x 1100 cm). national gallery of australia, april 1996.

How the body is represented and conceived of philosophically deserves critical attention today. For many, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how deeply connected humans are to the environment, and how dangerous it can be to conceive of humanity as separate or in control of “nature.” As humans continue to affect the ecosystem through industrial growth and expansion, we will experience more and more zoonotic viral pandemics, not to mention a rise in global crises resulting from climate change. To ultimately improve the state of the planet and sustain human—and all biological—life, we have to question our long-held assumptions.

Artworks such as Messager’s installation may appear to be irrelevant to issues like a global health and climate crises; however, most of us have experienced the way that powerful works of art can raise questions about the world and what we assume to be natural, neutral, or true. Art presents us with an aesthetic experience, removed from the world, and offers time and space to reflect on not only its meaning, but also how meaning is made.

The strength of visual art lies in its production of this critical distance, wherein our reflections might disturb even our most foundational personal beliefs. As we consider alternative ways of experiencing and conceiving ourselves and our world, we might not only think differently but act differently when taking into account social, economic, and political issues that concern the planet.

Kathryn Barulich is an art historian working toward a PhD at the UC San Diego Art History Theory and Criticism program. Her research is primarily focused on contemporary immersive installation and theories of haunting. This work takes up Gothic literature, phenomenology, site specificity, and the female uncanny. She is also interested in medieval animated sculpture such as the Cristo de Burgos, Victorian interior design, the French Revolution, and the intersections of the occult and technology. She earned a Masters degree in History and Theory of Contemporary Art at San Francisco Art Institute, with a focus on the linguistic and aesthetic strategies deployed by Dada artists working in interwar France. Previously, she studied Art History and French Language and Literature at Fordham University.